Just a reminder, MEQAPI stands for Monitoring & Evaluation, Quality Assurance, and Process Improvement.

Here’s the basic problem, and it can be deadly.

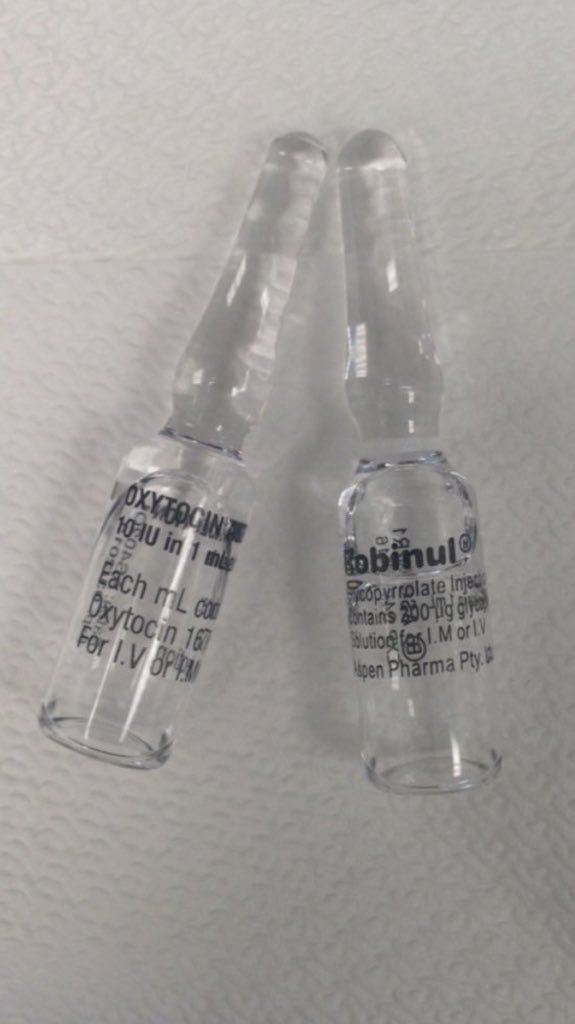

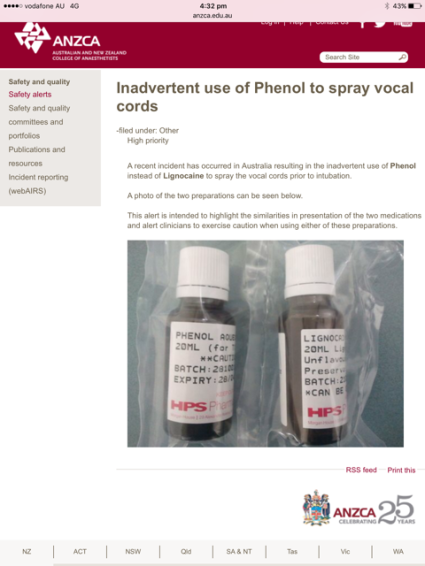

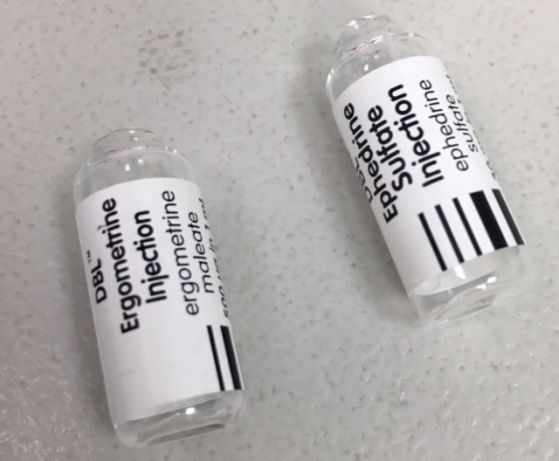

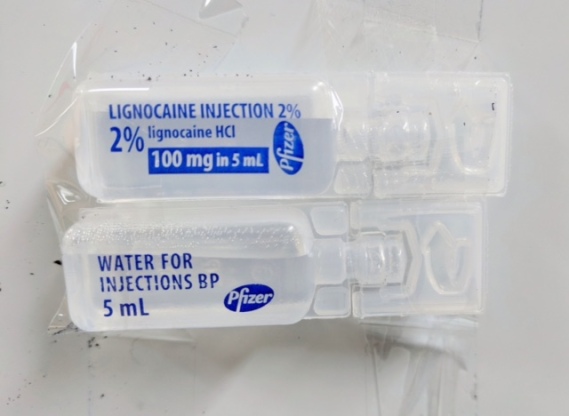

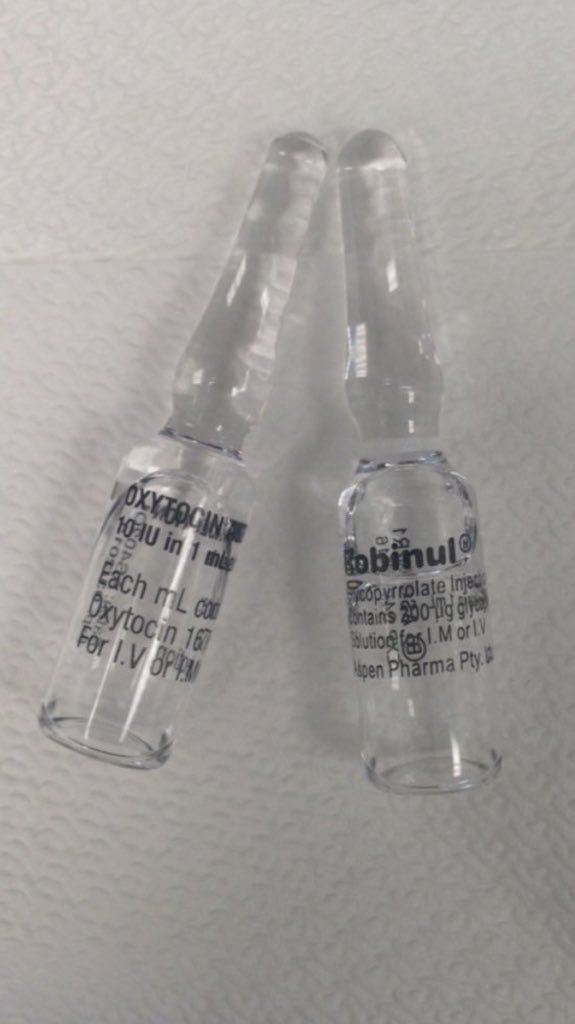

This image shows a medical error waiting to happen.

Medical error is arguably the third leading cause of death in the US, but we are not measuring medical error effectively, nor is medical error 100% avoidable. While many arguments can be made that the underlying research is imperfect, it is clear that medication error is a large contributor to injury and death, and also often unnecessary.

As was said in a previous blog “Medication errors result in missed opportunities, injury, and death. When the incorrect dose, incorrect medication, or wrong patient are in play, harm often results. Harm can also occur when incompatible combinations of drugs are administered – either because one drug reduced the efficacy of another, or because they worked similarly and resulted in an effective overdose”.

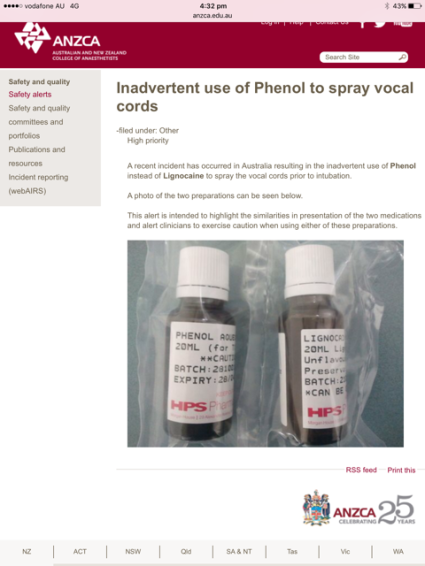

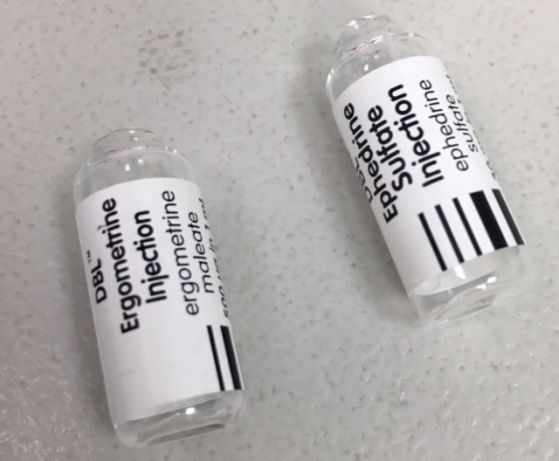

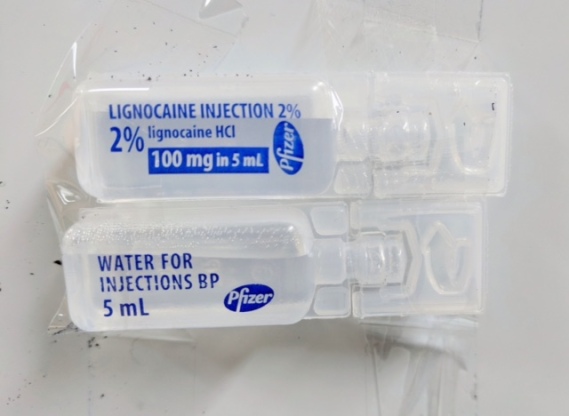

In an attempt to reduce drug-related harm, vendors and providers have tried many different fixes – ranging from making the fonts more readable, to electronic drug-drug interaction checks, to dispensing robots. However, the most obvious of all problems is that of indistinct medications – drugs and substances that can easily be misidentified or confused. This is especially so in the hurried and distracted environment in which medication is often dispensed, delivered, or administered.

Many medications are presented in forms that are indistinguishable without close scrutiny, with the result that many injuries and deaths are related to simple mix-ups between drugs or between drug concentrations.

These images courtesy of Dr. Rob Hackett (@patientsafe3)

In some cases of injury, the bottles of medication are identical, bar some very small lettering. This accident happens because we rely on nurses to be 100% vigilant, 100% suspicious of drug labels, 100% of the time. We assume that, like a robot, the nurse will never be distracted, never grow accustomed to a drug being in a known place, and never administering a drug before carefully rechecking the label against the patient and order.

While that is theoretically admirable, in practice we are just setting up the conditions for failure and blame. In many cases the products are bar-coded, but there we rely on ubiquitous availability of scanners and connectivity at the bedside, and 100% vigilance.

Even then, not all products that could be barcoded, are in fact barcoded, and again we rely on a very high degree of suspicion and awareness to avoid a catastrophe.

Even when the drug is correct, the concentration may vary. Again, we rely on 100% alertness by the nurse to avoid a disaster.

In some cases, the vendors add colored rings, or other (somewhat subtle) differences, but on the whole they rely on very small writing on the labels to distinguish plain water from Lignocaine, or Ergometrine from Epinophrine, or Xylocaine that is double the concentration between identical packages. In some cases, patients received a dose 100x the prescribed amount, simply because the concentrations were unclear. Often the only difference between a ten-fold difference in the same drug, or between entirely different drugs, is writing barely 2mm high.

What healthcare has NOT adopted, is the concept of Poka Yoke or “Mistake Proofing“. In simple terms, it should be almost impossible in practice to mistake two drugs or mistake two concentrations.

This requires standardization across all vendors and across all facilities. Barcodes should be on all medication containers, and the shape, color, and other identifying markings of drugs should be unmistakable, and consistent.

- Barcoding is a very effective way to reduce errors, but this must be universal, and it must be practical to scan at the bedside in every case.

- A cylindrical and clear ampoule should always be the same class of drug, and the concentration should be unmistakable, and a dimpled blue vial should always have the same drug, regardless of the vendor or location.

Medication safety requires that vendors and facilities not make up their own drug presentations or vary adoption of barcoding. Drug presentation should be based on what’s in the container and at what concentration it is, not based the manufacturing ease or marketing aesthetics of the vendor.

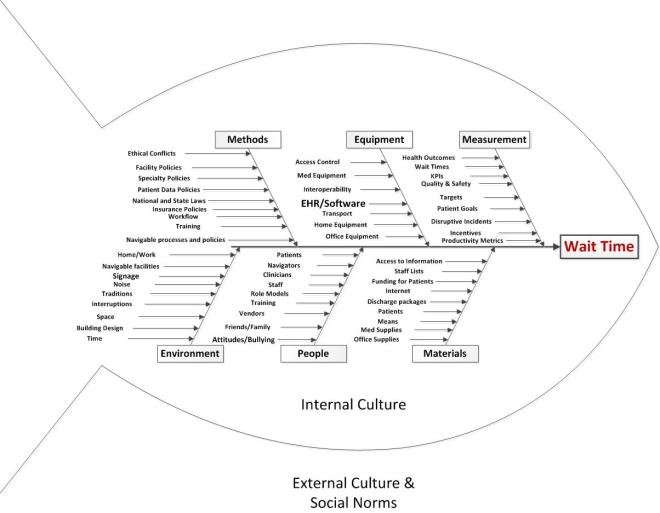

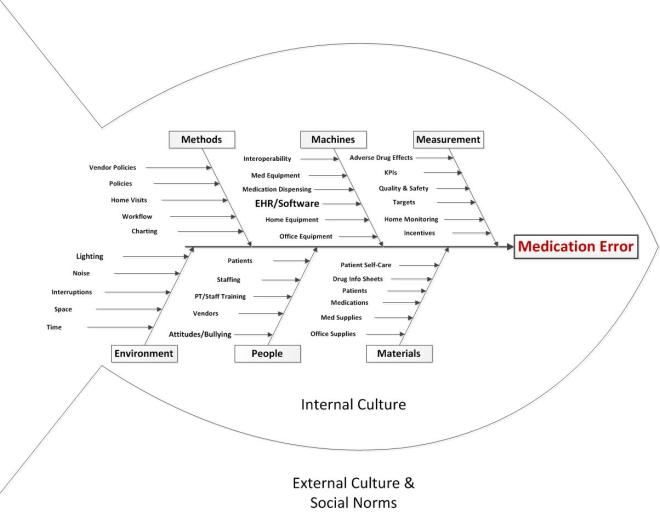

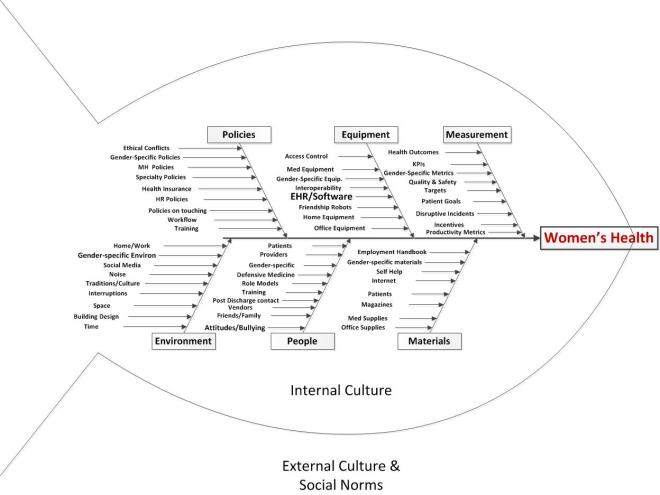

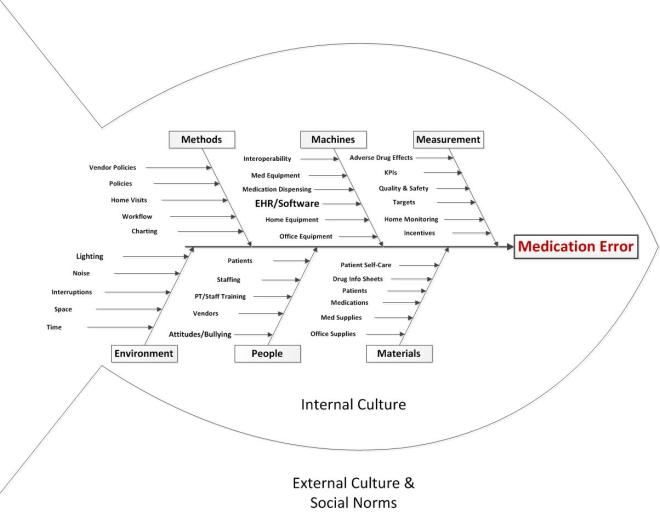

We will take a QI approach, and discuss the topic using each of the typical arms of the basic Quality Improvement Ishikawa diagram to guide and support discussion. An Ishikawa diagram will be provided ahead of time and during the chat.

Participants will bring their own experiences, perspectives, and expectations to the discussion, but the topics might break down something along these lines:

-

- Methods

- Policies: office, organization, or national policies, including MU, HIPAA, etc

- Workflow: how things are done including new patient onboarding, care provision, care coordination, ordering/prescribing, billing, patient transfer, etc.

- Insurance Models, payer systems

- Vendor policies and processes

- Home visits

- Machines (equipment, EHR)

- Medical or office equipment

- Home equipment specific to the patient condition

- Integration/interoperation with other office or medical systems, or user personal health records

- Medication dispensing systems

- People

- Staffing: sufficient and qualified staff

- Training: base training, ongoing training, CME, and patient or carer training

- Attitudes: staff attitudes to technology, adoption vs resistance

- Fatigue (especially alert fatigue)

- Materials

- Patients: as the “raw material” of the medical process. Patients may come with a range of attitudes, health problems, life situations, and ability to comply with treatment that are challenging and stressful.

- Supplies: medical or office

- Data: ability to securely share with correct patient, specialist, lab, etc

- Patient self-care materials including checklists and how-to instructions, contact information for questions, and self-care consumables

- Drug information sheets

- Measurement

- KPIs: operational metrics required by practice, local government, state, federal

- Quality and safety metrics

- Targets: set by practice, insurer, etc.

- Monitoring of home-care

- Adverse Effects reporting

- Environment

- Noise: distracting noises, sound levels too high, distractions, etc.

- Space: Cramped, uncomfortable work space etc.

- Lighting: too dim, shadows, flickering light, reflection

- Time: Too little time per patient or order, too little time in a day, too many demands

- Location: things where they should be relative to point of care and patient

Some of the authors of the works cited above may be responding to the following topics, and participants are invited to describe their experiences of medication errors, and offer their insights and observations.

Topics

- What Policies, practices, and laws increase or reduce the risk of medication errors from indistinct drugs

- What Equipment factors increase or reduce the risk of medication errors from indistinct drugs

- What People issues increase or reduce the risk of medication errors from indistinct drugs

- What Materials increase or reduce the risk of medication errors from indistinct drugs

- What Measurement factors increase or reduce the risk of medication errors from indistinct drugs

- What Environmental factors increase or reduce the risk of medication errors from indistinct drugs

Background

MEQAPI focuses on healthcare improvement, and in the spirit of shameless borrowing (and efficiency), takes existing perspectives from the IHI, AHRQ, and others.

To quote the IHI on what the Triple Aim encompasses:

The IHI Triple Aim is a framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement that describes an approach to optimizing health system performance. It is IHI’s belief that new designs must be developed to simultaneously pursue three dimensions, which we call the “Triple Aim”:

Improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction);

Improving the health of populations; and

Reducing the per capita cost of health care.

The six domains of care quality (STEEEP) mapped out by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) are foundational to healthcare improvement. All care, and by inference quality measures, should be focused on being Safe, Timely, Effective, Efficient, Equitable, and Patient Centered. We expand this to include Accessibility, STEEEPA.

The MEQAPI tweetchat aims to give voice to a broad range of stakeholders in healthcare improvement, and it embraces everyone from administrators to zoologists, and includes physicians, nurses, researchers, bed czars, cleaners, and yes, patients and care-givers.

http://www.meqapi.org

The Author and Moderator: Matthew is a principal analyst for healthcare improvement at the Washington D.C. based firm of Whitney, Bradley, and Brown (WBB), and is a strategic adviser and board member at the Blue Faery Liver Cancer Association. Matthew is a peer reviewer for the international journal of Knowledge Management Research and Practice, and blogs regularly for Physician’s Weekly.